NUYORICAN DREAMS

In October of 1931, The New York & Porto Rico Steamship Company mailed a letter to Eusebio Delerme to confirm his second-class passage aboard the Coamo. At the age of 24, he planned to migrate to New York City from Vieques, an island-municipality off of Puerto Rico’s eastern coast. As I looked further into the history of Puerto Rican migration to New York City, I learned that the Marine Tiger, Borinquen and Coamo steamships were “regular features in Puerto Rican life” during the early 1900s.[i] Travel lasted 4-5 days, but second-class passage meant cramped accommodations, meager meals, and other discomforts for the pioneers that established the first colonias in New York. In contrast, a menu from October 18, 1941 offered first class passengers aboard the S. S. Borinquen the following menu along with a selection of choice wines and after dinner coffee served in the “Smoking” or “Spanish” room:

Dinner Suggestions

Crabmeat Cocktail

Cream of Celery

Fried Fillet of Sole a la Meuniere

Patas de Ternera a la Andaluza

Roast Stuffed Capon with Giblet Sauce

Broccoli au Berre Carrots Vichy

Norma Salad

Pumpkin Pie Strawberry Ice Cream

Cheese

Demi Tasse[ii]

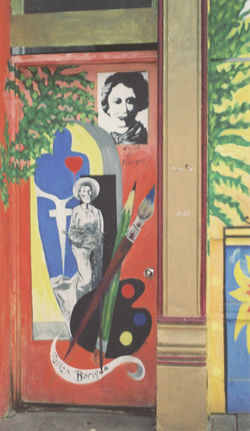

By the 1940s, however, Eusebio Delerme was running a bodega in East Harlem. My initial intention was to live and conduct anthropologic fieldwork in El Barrio, the East Harlem community where my grandpa, Eusebio Delerme, opened La Viequense on 22 East 112th street. His wife and eleven children, my father included, made the operation of the grocery store a possiblibly, and El Barrio was and continues to be home to four generations of Delermes. I planned to document the process of Latinization that resulted from the influx of migrants, and identify how families, like my own, attempt to preserve elements of their culture—from language to foodways—when migrating to a new destination. In the summer of 2001 and 2002, I photographed the streets of East Harlem and Wilmington, Delaware as part of a comparative study of cultural landscapes and Puerto Rican ethnic identity. The aesthetics of the landscape are best described in sociologist Juan Flores’ book:

A young Chicano friend, on a recent first visit to New York, shared with me some interesting impressions of the Puerto Ricans there and made comparisons with his own people in the Southwest. Of course he was reeling with the similarities between the huge Spanish-speaking neighborhoods of New York and Los Angeles where all your senses inform you that you are in Latin America, or that some section of Latin America has been transplanted to the urban United States were it maintains itself energetically, while interacting directly and in intricate ways with the surrounding cultures.[iii]

When I returned to El Barrio years later, however, the landscape was barely recognizable due to urban revitalization projects, the construction of luxury condominiums, and the dwindling Puerto Rican presence. East Harlem continued to change before my eyes between 2005 and 2010. Even members of my immediate and extended family followed the pattern reflected by the US census data and became part of the rapidly growing, new diasporic communities in the South. I decided to join the migration and moved to Orlando, Florida to begin ethnographic research.

[i] Félix V. Matos Rodríguez and Pedro Hernández, Pioneros: Puerto Ricans in New York City 1896-1948, (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2003), 11.

[ii] Félix V. Matos Rodríguez and Pedro Hernández, Pioneros: Puerto Ricans in New York City 1896-1948, (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2003), 20.

[iii] Juan Flores, Divided Borders: Essays on Puerto Rican Identity, (Houston: Arte Público Press, 1993), 182).

East Harlem, 2002

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

East Harlem, 2017

|  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |